Part I: growing up

My family wasn’t poor, but we weren’t well off. My parents didn’t have credit cards; if my Mom didn’t have cash in her wallet, we weren’t going to be buying anything.

My brothers and I wore hand-me-down clothes from friends and neighbors. Sometimes we received free lunch at school. Growing up, I wanted to play the saxophone; but I learned to play the clarinet, because a family member had an un-used instrument.

On occasion, we would go out to dinner; it was a treat. On occasion, we would go on vacation. We visited Plymouth Rock in Massachusetts, and Disney World in Florida, too.

My Dad worked at and retired from Pratt & Whitney, in Middletown Connecticut. He was an hourly machinist, and assembled the high pressure compressor for the PW4000 engine that powers wide-body aircraft, like the Boeing 777. Contract talks between the hourly union members and management took place in December. If the union and management didn’t reach an agreement, the union could vote to strike, which meant that my Dad wouldn’t go to work, and wouldn’t get paid. This always occurred right before Christmas, and I was old enough to notice my parents’ stress. I didn’t care about the Christmas presents, but rather, just paying the bills.

I started work at a young age, eight years old; I worked for my uncle, who lived down the street; he paid me a penny a minute to sweep the driveway. In high school, I worked for Joe, who lived on Cove Road in Lyme, which overlooks Hamburg Cove. He owned a forty-four foot sailboat, which was docked below his house. The boat had a nine foot draft, but the keel could be raised, to draft only four feet in shallow harbor. In the summer, I would sand the teak toe rail and hatches every month, and Joe would follow behind and re-varnish; some of the most gorgeous high-gloss woodwork you have ever seen. I wasn’t allowed to wear shoes on the boat, in order to not leave dirty footprints. The sailboat’s white, fiberglass deck could get very hot; I placed a towel under my knees, and would slide down the deck.

I bought a new clarinet in high school; a Buffett R13 for $1,000. I also bought a red Honda Scooter, an Aero 50 for $750; it had electric start, and had a one gallon fuel tank, with a separate oil injector, no need to mix fuel; it could reach speeds up to 40mph, and was less expensive than a car, but certainly, a cold ride in the winter.

My first federal tax return was in 1993 (1040EZ), after serving my first year in the Marine Corps, with taxable income of $5,000 as an E2, Private First Class.. After graduating from UConn in 2000, my first year salary at Pratt & Whitney was $35,000, at age 30.

I grew up with a scarcity mindset, a mindset that I’ve carried with me most of my life; I glued pennies together until I was thirty-seven years of age.

Part II: playing with FIRE

There is a lot of talk about financial independence, retire early (FIRE); save aggressively, and quit one’s job.

It helps to keep in mind the perpetual safe withdrawal rate, which is the amount that a person may extract annually from a portfolio. Typically, the safe withdrawal rate is not higher than 4%; while some professionals disagree, the perpetual safe withdrawal rate could be 2.5%, which is the rate that I typically use in my own calculations.

In this case, a $1,000,000 portfolio would allow an investor to safely extract $25,000 a year in perpetuity. In the United States, GDP per capita is $68,000 per year, which would require a portfolio of $2,720,000 to yield this amount of annual income.

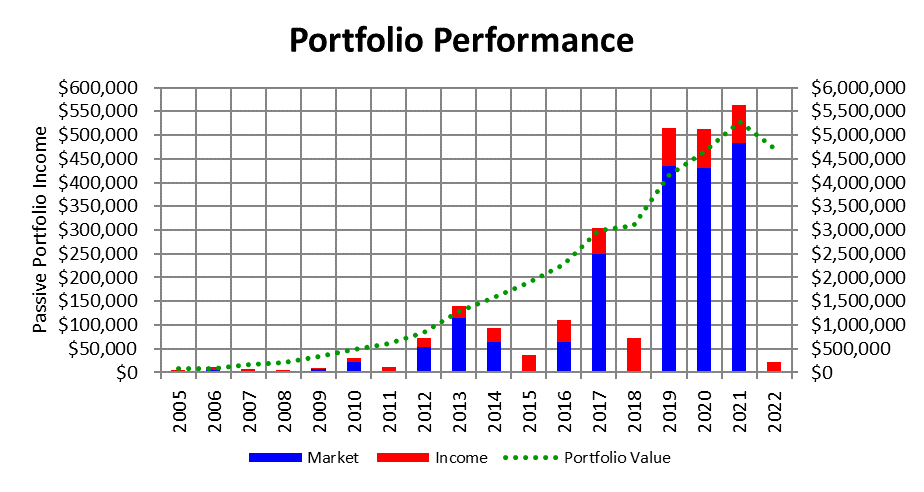

Some people believe that living on less than $100,000 per year is paltry, but understand that living on $100,000 per year would require a $4,000,000 portfolio. I monitor my portfolio’s passive income, noted in the chart below.

Part III: investing

I borrowed $100,000 for graduate school; $70,000 for two years of tuition, and $30,000 for two years of living expenses. After graduation, I used Dave Ramsey’s debt snowball to pay off the debt. I remember wanting to buy a new pair of skis, and I didn’t buy them until the debt was retired.

In 2007, I moved to Ottawa Canada, to become CFO for an early-stage biotech company. My salary was $200,000; my first six-figure salary at age 37. I didn’t live extravagantly, as my spending-saving habits were already firmly established.

In fall 2011, I moved from Ottawa to San Diego, to join my second early-stage biotech company. After the new year, January 2012, my portfolio reached $1,000,000; in 2014, the portfolio reached $2,000,000; about 80% of my portfolio is held outside of retirement accounts, due to the nature of some income distributions during my career.

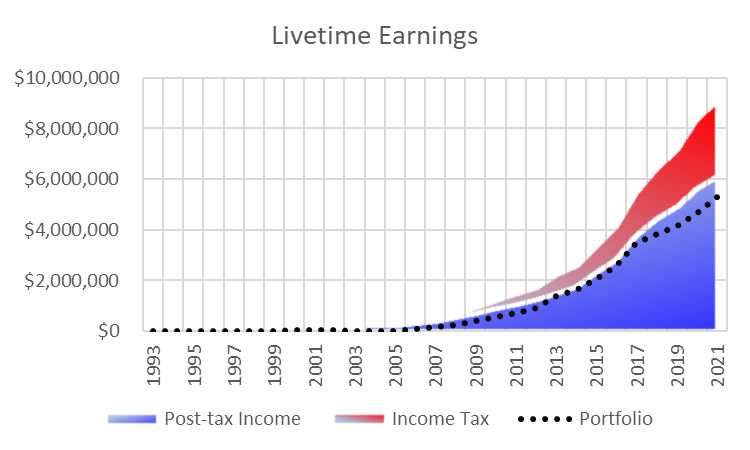

I track my lifetime earnings; saved 58% of every dollar, 32% paid to income taxes, and lived off 10%, noted in the chart below. I worked five years in Houston TX as CFO, for a private-equity firm; part of my compensation was carried interest, as part of each investment fund. I was required to co-invest with the limited partners, in what is a ten-year, illiquid investment. I anticipate another five years of carried interest distributions which contribute to my portfolio’s capital appreciation; about 5% of my net worth is tied-up in the co-investment. The chart below does not include my earned carried interest accrual; in this case, the income is earned, credited to my partnership account, taxed by the IRS, but not yet distributed in cash. When the cash distribution is subsequently made, the event is non-taxable.

Could have easily worked another decade in private equity, and likely doubled my net worth. But it wouldn’t change my standard of living; would likely still drive a Honda, and likely, still stay at hostels. Another dollar saved and invested, would be another dollar to give away.

Guy Raz hosts the podcast “How I Built This” and often asks guests if they achieved success due to luck, smarts, or hard work. My friend, John, who took JetBlue public, often suggests that he would rather be lucky than smart. I’m inclined to admit that I was simply lucky.

Invested with Vanguard since 1996, when I was stationed in Okinawa Japan. Appreciated Jack Bogle’s simple premise, investor owned, minimal expenses, invest in the entire market using low-cost index funds, without relying on an active fund manager.

Allocate 50% of my portfolio to equities and 50% to non-equities. I use dollar-cost averaging to invest each month, and use low-cost index funds, with the idea that fund managers often underperform. Average portfolio return is 8% after tax; portfolio allocation noted below:

- 40% Total Stock Market Index Fund: stock | the fund is designed to provide exposure to the entire U.S. equity market, including small-, mid-, and large-cap growth and value stocks, and could be used as an investors only domestic stock fund.

- 10% Total International Stock Index Fund: stock | the fund provides low cost exposure to both developed and emerging international economies; the fund tracks stock markets all over the globe, with the exception of the United States.

- 40% Intermediate-Term Tax-Exempt Fund: bond | the fund provides moderate income exempt from federal income tax; the funds average maturity is 6 to 12 years, with at least 75% of the securities held by the fund are municipal bonds in the top three credit-rating categories. This fund is held outside of retirement accounts.

- 10% Federal Money Market: cash | the fund provides current income, maintains liquidity, and a stable share price of $1; the fund invests at least 99.5% of its total assets in cash, or U.S. government securities. My cash position ensures that I won’t be forced to liquidate investments in the event of a protracted market downturn.

Part IV: trust

I recognize the amount of luck in terms of my financial condition. My intention is to be a good fiduciary – to not destroy the portfolio principal – but rather, to live off the portfolio’s passive income, and to gift the principal at time of death in a revocable trust.

Warren Buffet, when discussing passing on wealth to heirs, suggests giving “enough to do anything, but not enough to do nothing.”

- $4,000,000 is allocated to family; brothers, nephews, and nieces; the amount per person is enough to pay off a mortgage, or to buy a modest house.

- $1,000,000 is allocated to higher education; Regional School District 18 (Lyme-Old Lyme CT), Lyme Public Library (CT), MacCurdy Salisbury Education Foundation (CT), and the University of Virginia, Darden School of Business.

- $500,000 is allocated to the National Park Service Foundation, the donation arm of the park service; I enjoy visiting the National Parks; after visiting more than 60% of the parks and monuments, my impression is that the park service is under-funded.

- $500,000 to a dozen Zen Centers across the United States; some of these centers are large and established; some of these centers, are small, up-starts. Let’s assume that the Zen Centers are secular, and non-religious; in a period where people are glued to screens and devices, there is likely a benefit to meditation, an opportunity to be awake and aware.

Part V: cars

Recognize that the current car market is an anomaly, with some cars appreciating in value.

In high school, my dream car was a Honda Civic; likely, a pretty low bar. The car was affordable, reliable, and fuel-efficient; the car cost about $6,000 in 1984.

My first car was a used 1986 Subaru hatchback, with a four-speed manual transmission, and manual, crank-down windows. After my winter internship with Price Waterhouse (1999), I bought a new (red) Honda Civic coupe. I drove the car for twelve years, 250,000 miles, until it rusted out after the severe winters in Canada. The car still had the original clutch, too, which is amazing, given my NYC commute working for JetBlue. I replaced the car after moving to San Diego, with a 2012 Honda Fit, with steel wheels and a manual transmission.

I always wanted a BMW 3-series coupe, or M3 coupe. I remember test driving the 1-series coupe in Canada in 2008, the year that the car was released in North America. By the time that I could afford a BMW, I no longer wanted a BMW; perhaps, I appreciated how hard it was to earn and save a dollar.

The car that I most enjoy today is the Mazda Miata roadster, with the targa top. It’s not the fastest car, or most powerful car, but certainly one that is enjoyable to drive at legal speeds.

A car is not an asset; it is a depreciating liability with a put option (the option to sell the car at any time). An asset generates cash, for example, rental real estate, or a dividend-paying stock. In contrast, a house is not an asset, as it does not generate cash; it consumes cash, in the form of maintenance, repairs, and property taxes. Let’s say that you need to get from point A to point B.

Option 1 is to NOT buy a car; use public transportation, Uber, bicycle, walk. This is certainly more difficult in the United States, where public transportation is underwhelming.

Option 2 is to borrow money, and buy more car than one can afford. It’s all too easy to amortize the car into a monthly payment.

Option 3 is to use savings, and get out your checkbook, and purchase only as much car as one may afford. When I bought the Honda Fit, I went to the dealer and wrote a check for $15,000, the experience certainly makes a person think twice before buying a new car.

Option 4 is to use passive income – not principal – to purchase a car. For example, if a person has a $1,000,000 portfolio, and that portfolio generates $25,000 a year in passive income, than that is how much car a person may afford. The benefit of this approach, is that a person doesn’t “destroy” the underlying principal. In order to buy a $100,000 BMW M3, a person would need a $4,000,000 portfolio.

I believe that Dave Ramsey’s advice is best, when it comes to buying a car. Use cash, and buy only as much car as you can afford. If it’s a $1,000 “beater” car, than keep saving, and upgrade later. Dave suggests that due to depreciation, that a person shouldn’t buy a new car until they have at least $1,000,000 in liquid investments; many people would disagree.

Part VI: world travel

I know some people who take expensive “blow out” one week or two week resort vacations. My preference is to annualize the cost of a vacation, and compare to GDP per capita, or to a person’s annual salary or earnings. This to me is a better indicator of the sustainability of long-term travel.

For example, let’s assume that a couple visits a resort vacation for one week, costing $5,000. Annualized, this costs $250,000, and would require a $10,000,000 portfolio to fund.

For example, my daily cost of travel in Mexico (winter 2022) was $23 per day, which included lodging, transportation, food, and other expenses. Annualized, the cost is $8,500 per year. This would require a portfolio less than $350,000.

For me, lodging would be easier if I were married, or if I had a significant other. When it comes to travel, alcohol and meals out may quickly escalate travel expenses.

Part VII: Bitcoin

Warren Buffet discussed Bitcoin at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting in April 2022; he made a clear argument why he does not believe that Bitcoin is an asset, summarized below from a CNBC post; his insights are particularly clear and valuable, particularly, given the volatility experienced last week with the collapse of TerraUSD.

Bitcoin is not a productive asset; it does not produce anything tangible. Despite a shift in public perception about bitcoin, I still would not buy it.

Whether it goes up or down in the next year, or five, or ten years, I don’t know. But the one thing I’m pretty sure of is that it doesn’t produce anything.

If you said for a 1% interest in all the farmland in the United States, pay our group $25 billion, I will write you a check this afternoon; for $25-billion I now own 1% of US farmland.

If you offer me 1% for all the apartment houses in the country and you want another $25 billion, I will write you a check, it’s very simple.

Now if you told me you own all of the bitcoin in the world and you offered it to me for $25, I would not take it because what would I do with it? I would have to sell it back to you one way or another. It is not going to do anything. The apartments are going to produce rent, and the farms are going to produce food.

Assets, to have value, have to deliver something to somebody; and there is only one currency that is accepted. You can come up with all kinds of things – we could create Berkshire Hathaway coins, but in the end, this is money – holding up a $20 bill – and there is no reason in the world why the United States government would let it be replaced by Berkshire coins.

Part VIII: blogs

Intention of this post is not to change your mind; or to seek agreement; simply presenting a different, and likely, less popular point-of-view regarding personal finance.

I read several blogs from time to time; share below, if you find them beneficial.

Mr. Money Mustache tends to be binary; people tend to subscribe to his point of view, or disagree; that said, he provides an unvarnished point-of-view, that would allow people to FIRE; I enjoy reading his blog, and appreciate his honest and intelligent opinions.

Early Retirement Extreme is another blog that I enjoy; but acknowledge that it is indeed an extreme point of view.

Humble Dollar is written by Jonathan Clements, and other guest writers; Clements was the personal finance columnist at the Wall Street Journal for two decades. He’s not a proponent of FIRE, per se, but he does provide valuable advice to the average working American.

Can I Retire Yet is another practical blog, with useful calculators, written by Darrow Kirkpatrick, who retired at age 50 as an engineer, without being a dotcom millionaire.

Bogleheads is intended to honor Vanguard founder and investor advocate, John Bogle, and emphasizes starting early, living below one’s means, regular saving, broad diversification, simplicity, and sticking to one’s investment plan regardless of market conditions.