Part I: background

Always wanted to teach university. Didn’t want to invest five years to earn PhD; didn’t want to be career academic; after fifteen years as CFO in private equity, biotech industry, believed that I had something to share in the classroom – grey hair and wisdom. But I was wrong.

During 2019 sabbatical, had an intention that I would apply for “professor of practice” in accounting, a non-tenured, full-time teaching position, with salary and benefits.

University of Connecticut, where I studied accounting, had an opening; my family lives in Connecticut, too. As part of the application process, I taught a class to a panel of accounting faculty; titled the class “fun with numbers” where I illustrated the accounting assessment that I used to hire entry-level staff, and subsequently promote from within.

Part II: preparation

I spent the summer of 2020 preparing for the fall semester, including technology training, to be effective in the classroom, in particular, given the impact of the pandemic, and the risk that my classroom could revert from in-person to remote learning at any time.

I also developed my course content; PowerPoint slides, in-class examples, assignments, and quiz questions; didn’t use any prepared (canned) materials from the textbook publisher.

In Spring 2021, worked with the University’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETL), for a critical review of my course, given the student’s genuine disdain for my classroom. The consultant had very little to suggest that I was doing something “wrong.”

Part III: teaching

The experience was underwhelming. Mostly taught MBA students (75%); remaining students were undergraduates (juniors), accepted to the School of Business as an accounting major.

My first year of teaching was during the pandemic. I heard anecdotally that many students disliked remote learning, so I volunteered to teach in-person. Out of 25 full-time accounting faculty, only two faculty members volunteered to teach in-person.

Because of the pandemic, many international students left the United States. This put financial pressure on the university, and it appears that the university admitted almost anyone who applied to the part-time MBA program. It appeared to me that at least 20% of these students lacked the skills or ability to merit being in the classroom. I recall working out a problem on the whiteboard; a graduate student made the comment, “I don’t like this cost accounting.” I turned around and replied; “this isn’t cost accounting; this is high school algebra; we’re solving for X; and you’re enrolled in a graduate program.”

I’m not a fan of the two-exam course model (mid-term and final); it seems to motivate cramming instead of sequential learning. I eliminated the mid-term exam, kept the final exam, and instead, used weekly quizzes, to motivate students to keep up with the material. There were no multiple choice questions, or test bank questions from the text book publisher. I created every question, and every question was a calculation. If you work for a CFO, it’s unlikely that you’ll be asked a multiple choice question (ie. calculate cash flow from operations). Calculations were designed to give round numbers, or “softballs.” I often told students if they were getting “messy” answers, they were likely misguided in their work.

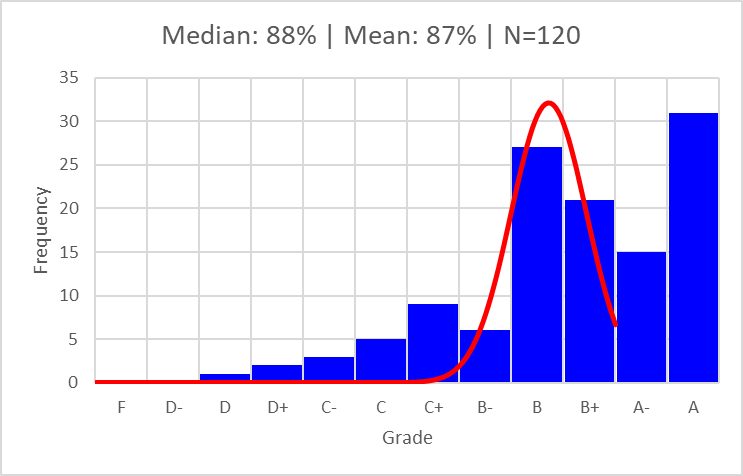

Based on student behavior, it appears that many students wanted a diploma, not an education. There was also a certain amount of grade inflation; as I was advised that the average course grade should be a “B” (84%).

I observed that many students weren’t curious; and was reminded of John Wooden, the UCLA basketball coach, who suggested, “it’s what you learn after you know it all that counts.” I tried to remind MBA students, that this degree would likely be their final, formal education experience; they would be “on their own” for forty years of career development. I taught in the Texas prison system, and observed that my incarcerated students were more curious than many of my university students.

When I was a student, feedback from professors was underwhelming. So I shared weekly feedback with students, so that they could compare their performance with the class. One of my bosses, Tom, used to explain this as “the gift of feedback.” Leaders share feedback because they care. My observation is that most students disliked this feedback. I question if this is the result that everyone wants to be “above average” or that everyone wants to receive an award for their work, and if so, it’s likely a damning future for the country.

At the start of every class, I reviewed material from the previous class; learning through repetition. Student recall was often underwhelming, like pulling teeth. At the end of every class, there was scored in-class participation, based on content from the last class, using iClicker. The intention was to motivate students to review their notes after class. I might repeat verbatim, a previous in-class example. Many students would get these questions wrong. Some students resented the in-class participation, because in order to earn the points (25 possible points out of 400 total points for the semester), they had to attend class, even though I didn’t take attendance.

In the spring semester, I volunteered to be an honors thesis advisor for a graduating senior. I went through the same process as an undergraduate, and felt that I could add value; I also hoped that it would be a redeeming factor for the academic year. I was wrong here, too. The student was completely disinterested in the assignment; confirmed by the professor responsible for this program at the end of the semester.

There was also evidence of cheating – some students don’t call this cheating – they call it collaboration. This Wall Street Journal article highlights cheating at the US Naval Academy; if cheating is rampant at one of the leading military institutions, what chance is there at the “average” university. I created five versions of each quiz question to mitigate cheating, and also created all new quiz questions for the spring semester.

MBA students were asked to write-up a one page executive summary, before each case discussion. One student’s solution was eerily consistent with the Harvard teaching note. I sent an open-ended email to the student, without judgment, to inquire, and didn’t even get a response. I subsequently filed an academic claim; the student put up no defense. To better understand academic misconduct, I volunteered to serve as a faculty member on an academic panel that adjudicates student cases of academic dishonesty.

For last scheduled class, shared “life lessons” including managing one’s career, and a far-reaching reading list; intention was to share some wisdom and insight; students were silent.

Chart below is full-year grade distribution for my 120 students. Three students didn’t pass, despite multiple opportunities to “fix and repair” their grades. If a student failed an assignment, s/he was provided the opportunity to revise and resubmit to earn a 70% (C-), with the intention that every student could pass the course. In the second semester, I allowed students to repeat each quiz, averaging the two grades, based on underwhelming quiz performance in the first semester.

There is nothing about accounting that can’t be learned by doing a Google search or watching a YouTube video. After teaching at university, I’m inclined to side with Peter Thiel, who suggests that university, for most people, is likely a waste of time and money.

Part IV: quitting

I received little support from other faculty. Faculty were either focused on their research (ie. to secure tenure), focused on their own class, or trying to negotiate the challenges of teaching during the pandemic. If I was the department head, I would have assigned a first-year mentor, someone to serve as a resource and sounding board; someone to observe the classroom, and share suggestions without judgment.

A colleague, Bill, called to understand how things were going. He has two children in school, and didn’t disagree with my observations, calling education, a “race to the bottom.”

During the semester, I kept an open email of bullet points, of what was working and not working in the classroom, and noted changes that I planned to make for the subsequent semester. At mid-semester, I obtained student feedback about what was working and not working in the classroom, and made real-time changes, when not unreasonable. Students completed university teaching evaluations at the end of the semester. Students also left excoriating public reviews on the website, Rate my Professor, as if I was a restaurant on Yelp.

I’m not convinced that students know what is best (for them). Why do I have to complete this assignment. In a similar manner, I’m not convinced that children know what is best (for them). Why can’t I have chocolate cake for breakfast. The easiest path may be the one of least resistance, but it doesn’t suggest that it is the path that we should follow. Teachers and parents both perform similar roles of teaching, guiding, and shaping.

I studied music at Ithaca College, and 8:00am first-year music theory with Dr. Mary Arlin. She was demanding to say the least; she cared about the music; she cared about the students. Thirty years later, she’s one of the people I remember who deeply influenced my life.

Cost accounting was a required class for both undergraduates and MBA students. Reviewing feedback at the end of the semester, at least 60% of students didn’t want to take the class. This is pretty difficult to counter. When I was a student, most students didn’t like cost accounting. I volunteered to teach the class, believing that I could make the material relevant given my professional experience; I was wrong.

I suggested to the department head, that MBA students have only one semester of accounting required, not two (financial and cost accounting), structuring the class with eight weeks of financial and four weeks of cost. One of the major employers in Connecticut, who also pays for many students’ part-time MBA tuition, likely insists that the program have a required course in cost accounting.

I surmised that if I returned for a second year of teaching, that it would be marginally better, but not fundamentally different.

In the spring semester, my last final exam was on a Friday evening; I graded exams and uploaded final grades to the registrar. On Monday morning, I reached out to my boss, the department head, and resigned. We discussed for an hour; he asked me to speak with other faculty that week, to see if they could influence my decision.

Most faculty didn’t disagree with my observations; further, many faculty remained with the university because they were vested; only a few years to go until retirement; or the “sunk cost” of investing five years for a PhD.

Distinct from many career academics, I hired and fired people, and built teams for more than twenty years. It is disingenuous to lower the bar in the classroom.

Also distinct, from many career academics, I am financially independent, and didn’t need a paycheck. I wanted to teach; I wanted to make a difference; I wanted to “dent the universe.”

My perception is that the university is a self-serving institution; it’s purpose is to conduct independent research, and serve itself. I’m not convinced that the purpose of university is to educate students; this is likely a residual, end-product; like sawdust at a lumber yard.

Some people suggested that I focus on the 5% of motivated students, and ignore the rest – ignore the majority. I fundamentally disagree. What if you asked someone to paint your house, and only 5% of the house was painted.

I used to tell my teams, for a given week, 80% of the days should be good, rewarding, productive days. This is the majority of the time, because sometimes, things go wrong, outside of our control. Teaching should be the same; we should reach the majority of the students – at least 80% – anything else is a waste.

In a large, Fortune 500 company, there are many places for underperforming employees to hide. In a small company, there is nowhere to hide. Everyone has a unique role; everyone has to perform. An underperforming employee is a burden on a “good” employee; a good employee has to work harder and longer. As a team leader, an underperforming employee, is a disservice to the team. I never weeded out an underperforming employee to be mean – always extended training, coaching, and feedback – but everyone has to perform at a level consistent with the team.

My friend, Greg, teaches at a leading, public university, and advised me that I would be punished by my students if my class was materially different, or materially more difficult. Greg was correct; my classroom was too different from my faculty peers.

Seiji Ozawa, a Japanese conductor, was music director of the Boston Symphony for 29-years. He often cited the Japanese proverb that “the nail that sticks out may be hammered down.”

I played sports as a child, and taught that quitters never win, and winners never quit. But I don’t regret quitting; I don’t regret trying; I always wanted to teach, and the feedback was deafening, and impossible to ignore. Until this point during my career, I never quit too soon.

Part V: theory

Annie Duke was a professional poker player; before following this career path – quite by accident – she worked on a PhD in psychology and cognitive linguistics. Since retiring from the poker circuit, she has shared a number of insights about psychology, and in particular, when to quit (or fold – which is critical), focusing on cognitive-behavior decision science.

Adam Grant, a business professor at the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School of Business, focuses on organizational behavior, also has valuable insights into the escalation of commitment fallacy – a human behavior pattern, where current behavior is continued, instead of changing direction, despite increasingly negative outcomes. Adam suggests that people should celebrate failure – because it’s valuable feedback. Like a failed hypothesis in the laboratory; trying something new – failing miserably – is useful information.

Author Seth Godin reminds us that a sunk cost, is the cost paid by the past self, and gifted to the future self, because the gift that doesn’t have to be accepted. In other words, a person may choose to quit and walk away, not being obligated or tied-down by the sunk cost.

Jim Collins, celebrated author of Good to Great, suggests that many successful companies are those that constantly reiterate. My friend Jani, often cites Netflix as a prime example; the company has had at least three business models that have changed with time. When the company started out, a person could get DVDs via mail; at another time, a person could stream content at home; and today, the company is largely an independent production company, creating its own content.

I often encouraged people on my teams to “fail fast.” In other words, try something (ie. an assignment or project), and quickly get to the point of feedback; something is working, or something is failing, and use that information to change direction, if necessary.

In the end, we make the best possible decision with imperfect or missing information. In my situation – the status quo – remaining at university, was the easier decision, but likely misguided. Quitting is hard, it’s often difficult to escape gravity’s pull. Instead, I appreciated the valuable feedback, celebrated my (stinging) failure at UConn, and made the difficult decision to move on. Also noted that quitting in subsequent years, would likely become more difficult.

I’ve read Sun Tzu’s, The Art of War, many times; “if you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.” The only good part of university, was being a state of Connecticut employee, and receiving superlative medical benefits. But to remain at the university, for just this benefit, seemed disingenuous.

Failure isn’t fatal. Failure isn’t final. Don’t need to fear failure. What’s next; I don’t know; will continue to explore, experiment, reiterate, and embrace fear.

Part VI: contraindications

Teaching at UConn motivated me to look back at my college experience. In hindsight, it was likely misguided to get an internship as an undergraduate and graduate student. Most people suggest getting “valuable” work experience. If a person is going to be in business, it seems far more valuable to do something entrepreneurial; try > fail > reiterate > repeat. It’s far easier to try and fail at age 20, or age 30, than at age 50. It’s a bit like downhill skiing; it’s easier for a five-year old child to fall down, and get back up, than for a 50-year old adult.

The other challenge, is that in business school, it’s suggested to “go big or go home.” Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google. Likely walk away from many good, small ideas, because they are not big enough, or bold enough. Dent the universe, or, go home.

And then there is the character Yoda, from Star Wars, who suggests that “there is no try, only do.” And this message seems misguided, at times, too. Not everyone is going to become President; not everyone is going to win an Olympic gold medal; but this doesn’t mean that there isn’t merit in trying, that there isn’t merit in the process.

As part of my estate plan, I set-up a revocable living trust a decade ago. This ensures that assets held outside retirement accounts, may quickly pass to beneficiaries, without getting delayed in probate. The gifts in a revocable living trust may be revoked at any time while the benefactor (me) remains alive; I typically update the trust once or twice per year.

After completing my enlistment in the Marine Corps, I was grateful for my accounting education at the University of Connecticut. As such, I named a $350,000 gift in the revocable trust to the School of Business, as part of a $1,000,000 gift towards higher education.

After teaching at UConn, I seriously questioned the value of this gift, and was gravely concerned that the gift was not wisely allocated. At the end of the academic year, I was concerned about making a knee-jerk decision to revoke the gift, so I reduced the gift by half.

In December 2021, I revoked and reallocated the entire gift, with $100,000 going to the Lyme Public Library, and $250,000 going to the MacCurdy Salisbury Education Foundation. I was a beneficiary of both organizations growing up, and feel that this allocation may be more beneficial to future generations.